MCEN

Mathematical, Computational and Experimental Neuroscience

The neuroscience program at BCAM investigates the mechanisms of information processing and storage in the brain, their disruption in disease, and develop technologies to treat neurodegenerative disorders.

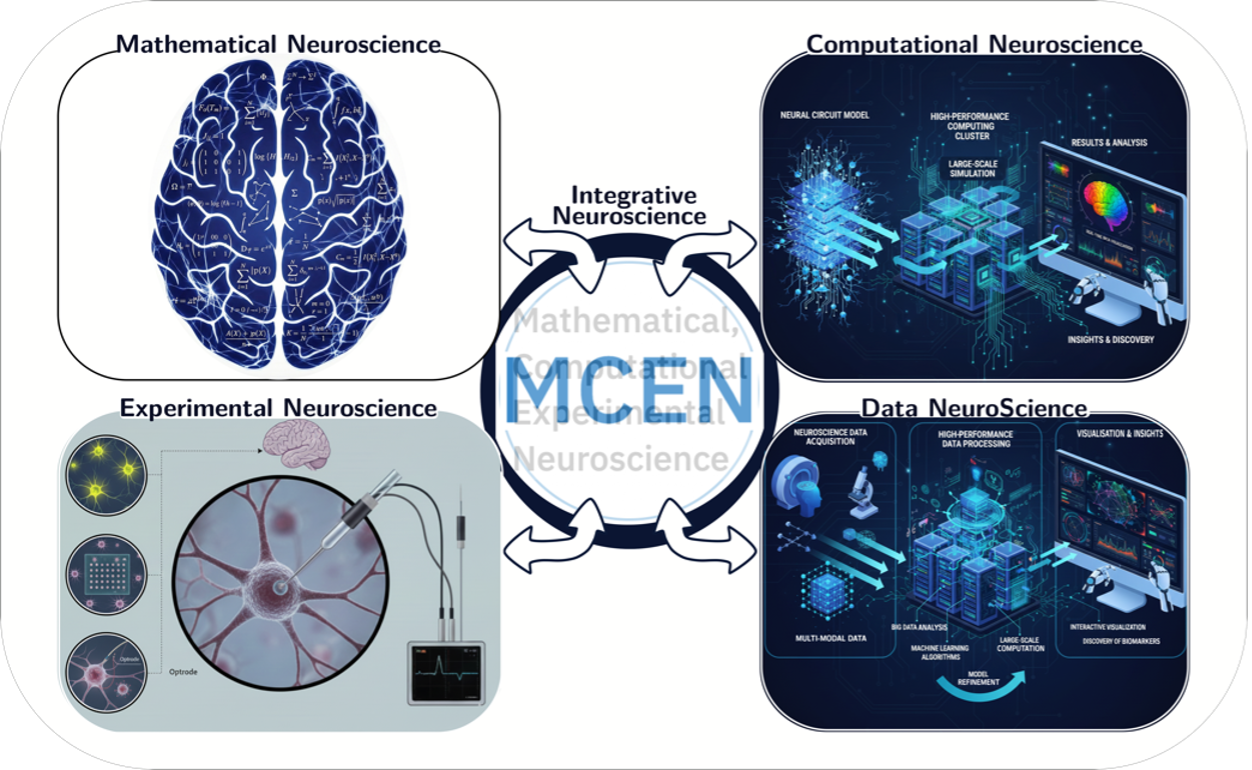

The MCEN research group conducts innovative work at the interface of mathematical, computational, and experimental neuroscience, with the ultimate goal of understanding brain function and neurodegenerative disease. The insights gained from this research have the potential to drive next-generation technologies and clinical therapies. MCEN’s work is organized into four synergistic research pathways (Fig.1), namely: 1. Mathematical Neuroscience; 2. Computational Neuroscience; 3. Experimental Neuroscience and 4. Data NeuroScience. These pathways are outlined below.

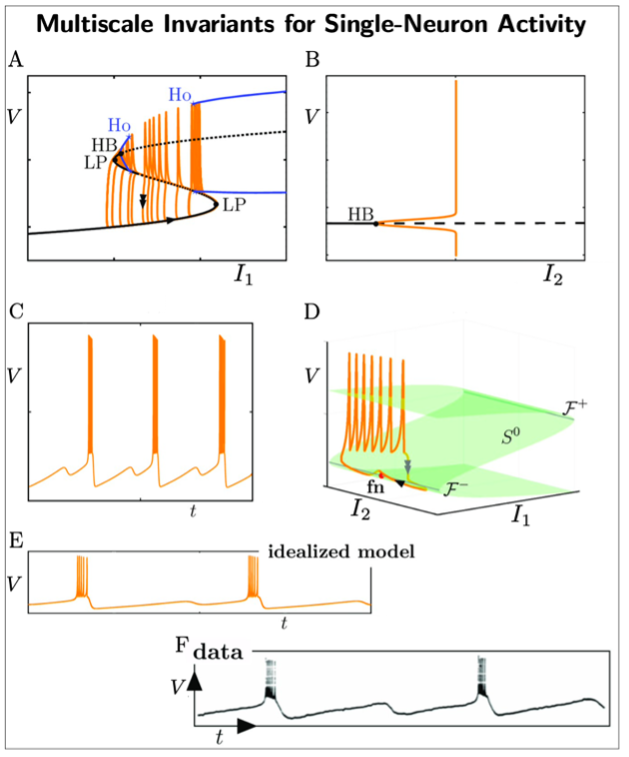

Mathematical Neuroscience: This line of inquiry aims to identify fundamental mathematical principles underlying neural activity across spatial and temporal scales. Analogous to mathematical physics, this research seeks deep mathematical structures—algebraic, topological, geometrical, and dynamical—that express invariants that are stable across different measurement modalities and enable the formulation of unifying principles. These principles should rest on biophysics. From these principles, entire families of neural models can be generated to explain neurophysiological processes with quantitative agreement.

A key example of this approach is our multiscale analysis of single neuron activity (see Fig.2). By virtue of geometric singular perturbation theory, we unveil mathematical structures and invariances (dynamical, geometrical) underpinning single neural activity. In particular, different combinations of the following objects: locally invariant (slow manifolds), invariant manifolds, folded singularities, bifurcation points, lead to an entire family of observable neural dynamics. More critically, these invariant objects can be connected to first principles of biophysics and to experimental observations. This has enabled us to extend previous approaches and we are now able to describe a larger family of complex single-neuron activity involving slow and fast timescales [1]. This opens new avenues to capture information content and invariants in electrophysiological data.

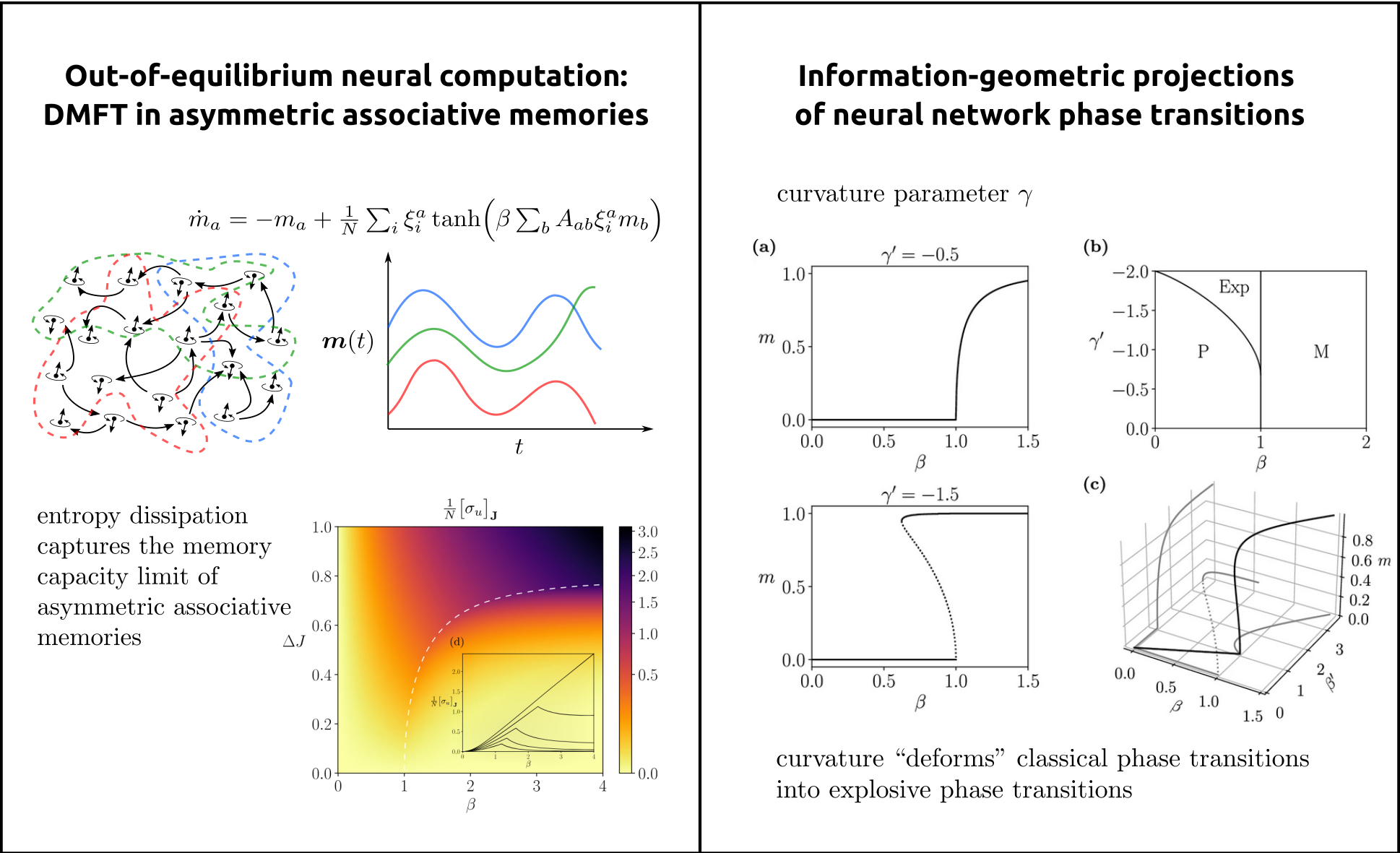

Computational Neuroscience: This line of research bridges mathematical and experimental neuroscience by developing theory-driven, mechanistic models that treat neural activity as a complex physical process operating far from equilibrium. These models are designed to generate testable predictions, reveal underlying circuit architectures, inform experimental design, and distill theoretical principles that feed back into mathematical neuroscience. Ultimately, the goal is to establish overarching principles of neural computation—including coding, learning, memory, and decision-making—from which new bio-inspired AI technologies, neuromorphic circuits and therapeutic strategies can be derived.

Methodologically, we draw on dynamical systems theory, statistical physics, information theory, and complex-systems modeling to characterize how large-scale neural networks give rise to flexible and adaptive computation [2,3,4]. We treat neural processes as open systems operating far from equilibrium and seek macroscopic principles that govern their behavior, including phase transitions, critical phenomena, higher-order interactions, and thermodynamic signatures of computation. As an example, in (Fig.3, left), we illustrate collective neural dynamics in an asymmetric associative memory, where nonequilibrium interactions organize activity into sequential memory states connected by directed transitions, leading to oscillatory activation of stored patterns rather than convergence to fixed-point attractors. Entropy dissipation captures the memory capacity limit from storable. to non-storable transitions.

A key direction is the development of general mathematical frameworks, grounded in information geometry, to uncover the deep structure of higher-order interactions in collective activity [5]. In this framework, types of neural dynamics are viewed as points on statistical manifolds, where differential geometric properties such as curvature encode high-order dependencies and invariants of the system (see Fig.3, right). By developing analytic tools encoding these geometric structures, we derived families of tractable neural network models that capture complex interaction patterns and emergent behaviour from minimal assumptions, revealing geometric signatures that go beyond conventional dynamical systems approaches.

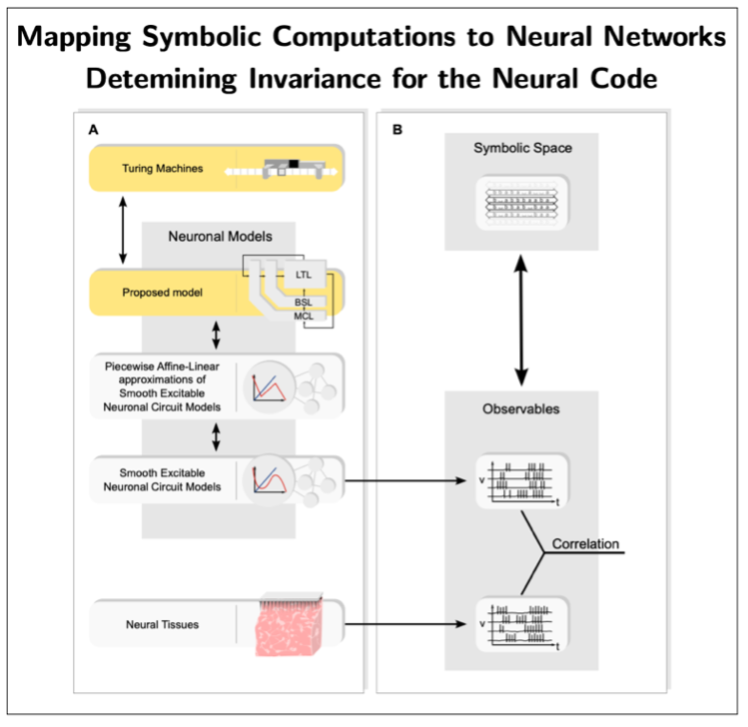

Moreover, we are developing an alternative mathematical and computational framework—Neural Automata—aimed at enabling the design of biologically plausible neural networks capable of symbolic processing [6,7]. The overarching goal is to provide a principled foundation for explainable, bio-inspired AI with symbolic interpretability, as well as to inform the design of neuromorphic circuits and the decoding of the neural code. To this end, the Neural Automata framework develops a representation theory that maps symbolic computations (e.g., Turing machines and related formalisms) onto neural networks—thus far focusing on artificial neural networks—thereby endowing them with explicit symbolic interpretability (see Fig. 4). This line of research is still in its infancy. A key next objective is to extend these mappings to biologically plausible network architectures, which, if successful, would enable the extraction of neural codes by establishing systematic correspondences between network observables and empirical brain data (see Fig. 4).

Experimental Neuroscience: At our NeuroMath Lab, the overarching vision is to tightly interface mathematics with experimentation in order to develop next-generation instrumentation with substantial scientific and technological impact, as well as significant socio-economic potential.Central to this effort is the design of novel, controlled experiments grounded in mathematical insights, aimed at uncovering neuronal properties—such as invariants—or dynamical processes that are inaccessible using standard experimental paradigms. Revealing such hidden structure has the potential to bridge existing knowledge gaps, yield fundamental insights, enable the falsification of prevailing computational models, and drive the development of novel technologies.

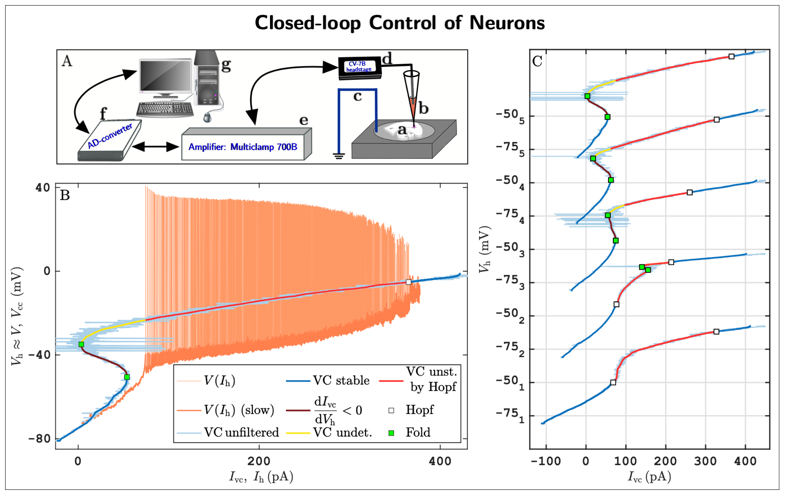

As a concrete example, we are pioneering a new experimental methodology that integrates mathematical feedback control, bifurcation theory for dynamical systems, and pseudo-arclength numerical continuation to robustly track solution branches of nonlinear systems directly from noisy experimental data. This approach enables the direct identification of both stable and unstable neuronal states, as well as their stability boundaries, in living neuronal cells. The method has been implemented within the dynamic-clamp electrophysiology framework, which allows precisely tunable, real-time, bidirectional communication between a computer and biological neurons.

A first implementation of this approach (Fig. 5; see also [8]) reveals previously inaccessible neuronal states and stability boundaries in living neurons, providing the first experimental confirmation of long-standing theoretical predictions. These results demonstrate that experimentalists can now probe neuronal subsystems—such as ion channel dynamics—with a level of precision unattainable using standard pharmacological or acquisition techniques.

In the long term, our goal is to develop novel closed-loop machine–brain interfaces [9,10] that enable both the understanding and control of neural dynamics in health and disease. For example, we envision next-generation deep brain stimulation devices capable of tracking stability boundaries between normal and pathological brain states and applying real-time feedback control to prevent transitions into epileptic seizures.

Data NeuroScience: The overarching vision of this research program is to establish a principled, interpretable, and predictive framework for understanding the brain by uncovering invariant structure–function relationships across scales, data modalities, and conditions. Rather than treating neural data as isolated high-dimensional observations, we aim to reveal the underlying structural–dynamical organization that governs how neural systems represent information, adapt, and give rise to cognition in both health and disease.

Central to this vision is the idea that brain function emerges from the coupling between structure and dynamics: anatomical, cellular, and molecular constraints shape the space of admissible neural dynamics, while collective neural activity reveals the functional organization of computation. By identifying mathematical invariants—geometric, topological, dynamical, and informational—that remain stable across experimental contexts, individuals, and measurement modalities, we seek to uncover universal organizing principles for the emergence brain function. This invariant-based perspective provides a unifying language for interpreting large-scale neural data, enables robust generalization across conditions, and offers a foundation for mechanistic explanations that go beyond prediction. Ultimately, this framework will support the discovery of interpretable biomarkers, principled disease classifications, and quantitative measures of cognition, while informing the design of closed-loop neurotechnologies and bio-inspired artificial intelligence.

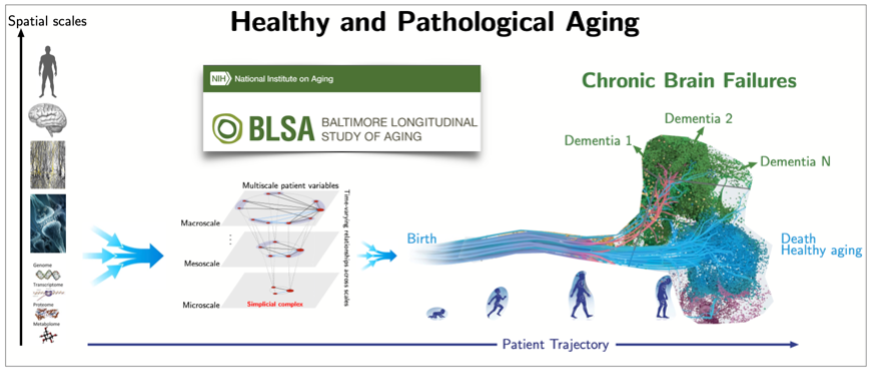

As an example, we have just initiated an international collaborative project on brain aging, which aims to determine biomarkers of normal and pathological aging from human life-span multi-modal data, see Fig.6 and [10]. The ultimate goal is to enable the development of novel clinical therapies (including drug design) and preventive clinical interventions to enable healthy aging and reduce public health care costs.

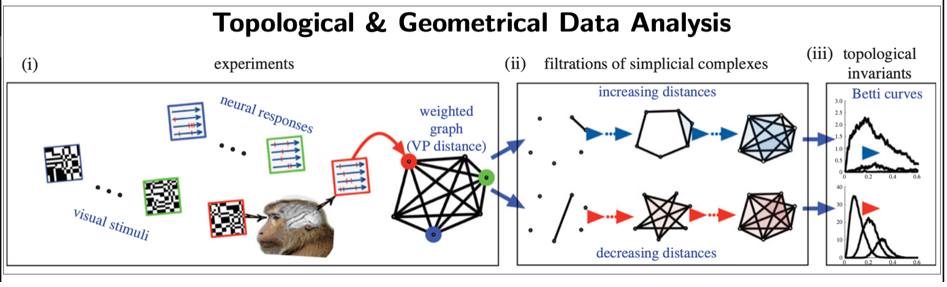

Beyond traditional methods in data science (e.g. statistical, machine-learning), we have been developing data novel methods based on: 1. Dynamical systems theory (e.g., Poincaré recurrence theorem) to extract metastable states (i.e., quasi-invariant states) from brain data [12]; 2. Topological and geometrical data analysis [13,14] (see Fig.7) to extract geometrical and topological invariants.

References:

[1] Desroches, M., Rinzel, J., & Rodrigues, S. Classification of bursting patterns: A tale of two ducks. PLOS computational biology, 18(2), e1009752. (2022).

[2] Aguilera M, Igarashi M & Shimazaki H. Nonequilibrium thermodynamics of the asymmetric Sherrington–Kirkpatrick model. Nature Communications 14, 3685 (2023).

[3] Aguilera M, Millidge B, Tschantz A & Buckley CL. How particular is the physics of the free energy principle? Physics of Life Reviews 40: 24–50 (2022).

[4] Aguilera, M, Moosavi, SA & Shimazaki H (2021). A unifying framework for mean-field theories of asymmetric kinetic Ising systems. Nature Communications 12, 1197.

[5] Aguilera M, Morales PA, Rosas FE & Shimazaki H. Explosive neural networks via higher-order interactions in curved statistical manifolds. Nature Communications 16, 6511 (2025).

[6] GS Carmantini, P beim Graben, M Desroches and S Rodrigues. A modular architecture for transparent computation in recurrent neural networks. Neural Networks 85: 85-105, (2017).

[7] Uria-Albizuri, J., Carmantini, G. S., beim Graben, P., & Rodrigues, S., Invariants for neural automata. Cognitive Neurodynamics, 18(6), 3291-3307, (2024).

[8] Amakhin, D., Chizhov, A., Girier, G., Desroches, M., Sieber, J., & Rodrigues, S. Observing hidden neuronal states in experiments. PLOS Computational Biology, 21(12), e1013748, (2025).

[9] N Sefati et. al., Monitoring Alzheimer’s disease via ultraweak photon emission, iScience 27, (2024).

[10] V Salari, R O'Connor, S Rodrigues, D Oblak, Editorial: New approaches in Brain-Machine Interfaces with implants, Front Neurosci 18, (2024).

[11] Fulop T, Desroches M, A AC, Santos FAN, Rodrigues S. Why we should use topological data analysis in ageing: Towards defining the "topological shape of ageing". Mech Ageing Dev. (2020), doi:10.1016/j.mad.2020.111390

[12] beim Graben P., Jimenez Marin A., Diez I., Cortes JM, Desroches M, Rodrigues S, Metastable resting state brain dynamics, Front Comput Neurosci 13, (2019).

[13] Guidolin, A., Desroches, M., Victor, J. D., Purpura, K. P., Rodrigues, S. Geometry of spiking patterns in early visual cortex: a topological data analytic approach. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 19(196), (2022).

[14] Barros de Souza D, Teodomiro J, Santos FAN, Jost J, Rodrigues S. Efficient set-theoretic algorithms for computing high-order Forman-Ricci curvature on abstract simplicial complexes. Proceedings of the Royal Society A 481: 20240364, (2025).

Code and data reproducing the paper "A unifying framework for mean field theories of asymmetric kinetic Ising systems"

Authors: Miguel Aguilera

License: GPLv3.0